et enfin l'ancètre des habitants du Sud est marocains a été retrouvé dans les chantiers de faussilles dans le téritoire des Ait Bourek à l'est de la Ville d'Erfoud.lire le texte récupéré sur www.errachidia.org Confirmation de l'authenticité du petit crâne du Tafilalet |

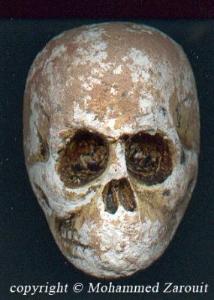

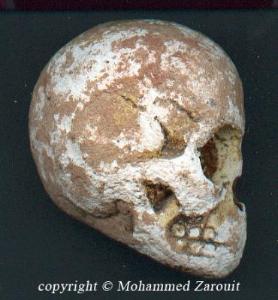

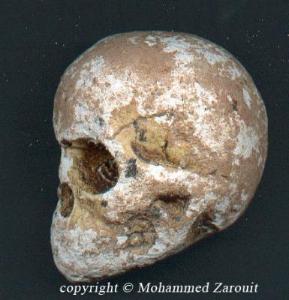

| Le crâne de taille minuscule, découvert par un jeune paléontologue amateur en juillet dernier près d'Erfoud sur un site réputé pour ses fossiles d'Orthocères et de Goniatites, a été authentifié par des scientifiques. "C'est un crâne authentique et non un objet façonné", a assuré Dr Alaoui Abdelkader, radiologue et directeur de l'hôpital Moulay Ali Chrif, après avoir effectué un examen tomodensitométrique (scanner à rayon X). Le crâne dont la taille ne dépasse pas celle d'une pomme (circonférence 18,4 cm) a été découvert sur un terrain de Dévonien, ce qui donne une idée sur son âge qui pourrait dater de 360 millions d'années. "Les résultats sont fascinants et je suis vraiment étonné devant la plasticité biologique" de ce crâne, a affirmé Dr Alaoui, soulignant que les informations numériques (densités) issues du scanner sont conformes aux valeurs de densité osseuse". "Je crois que ce crâne cache encore des surprises", a-t-il estimé en faisant référence à l'éventuelle fossilisation du cerveau. Les images issues du scanner, révélant une architecture particulière et une densité très faible, laissent espérer de trouver un cerveau fossilisé "et non un banal moulage endocrânien naturel", a soutenu Dr Alaoui. M. Mohamed Zarouit avait avancé, lors de l'annonce de sa découverte, que le crâne fossilisé est du genre Homo. A en juger par les dents de sagesse non usées, il s'agit bien d'un adulte, avait-il soutenu. Le crâne présente les caractéristiques du genre Homo, comme en atteste la position du trou occipital (centrée), la mâchoire (courte, parabolique), l'angle symphysaire (obtus, se positionne en retrait), le front (haut et bombé, comme l'arrière crâne) et la formule dentaire (estimée à 32 dents, insérées verticalement), avait-il précisé. Une étude préliminaire sur le spécimen avait été publiée dans la revue scientifique Bipédia on line N 25. Interrogé par la MAP sur le procédé utilisé pour dater le spécimen, M. Zarouit a expliqué s'être basé sur un procédé de datation bio chronologique, ajoutant que la même méthode a été adoptée pour dater le fameux crâne de Sahelanthropus tchadensis (6 à 7 millions d'années) qui a été également retrouvé à même le sol en dehors de toute connexion géologique. Intéressé par le sujet, M. Eddahby Lhou, ingénieur chercheur en géologie appliqué et membre du groupe de recherche en géologie appliquée (GRGA) à la faculté des sciences et techniques d'Errachidia, a indiqué qu'une étude topographique et stratigraphique du site ainsi qu'un relevé détaillé de la faune qui y est associée seront bientôt annoncés. M. Eddahby a toutefois souligné la nécessité de lier les études sur le crâne en question aux fouilles entreprises sur les sites de Sijilmassa. Source : MAP | avmaroc.com Photo du petit crâne   photo du Paléontologue amateur M. Mohamed Zarouit  |

| 13/06/2006 |

mercredi, juin 28, 2006

ENfin l'ancétre des Habitants de Tafilalet retrouvé

Posted by

Arehal

at

11:54 AM

![]() 0

comments

0

comments

samedi, juin 24, 2006

Settin

un numero maudit par le "verbe" marocain. "setta u ettin kshifa" "zid setta 3la settin" , "...hiyya settin", par fois " settash".

un numero maudit par le "verbe" marocain. "setta u ettin kshifa" "zid setta 3la settin" , "...hiyya settin", par fois " settash".

c'est un numero qui passe sa vie en dehors des villes, dans des millieux delaisses.

Photo courtesy: Moha arehhal, inebdu n 2005.

Posted by

m. bouba

at

3:46 AM

![]() 0

comments

0

comments

mercredi, juin 07, 2006

Marock est-il marocain?????

Marock est il marocain ?

Moha Arehalin "Le Monde Amazigh" Juin 2006

Marock, le titre d’un film, qui ne cesse d’alimenter les discussions et sur les une des journaux que sur les forums électroniques. Ce film, le premier long-métrage d’une marocaine de la classe bourgeoise, vivant à l’étranger, a été présenté dans deux festivals de film au Maroc, celui de Casablanca et celui de Tanger. Il a été sélectionné dans le festival de Cannes dans la section « certain regard ». Lors du lancement de ce film dans les salles du festival de Tanger, un réalisateur nommé « Mohamed Asli » a ouvert le feu sur le Film. Au lieu de la critique, le réalisateur du film « à Casablanca, les anges ne volent pas » a attaqué farouchement le film sur un fond idéologique basé sur les « valeurs » de notre peuple. Il a même ajouté que la réalisatrice du film Marock est employée par les occidentaux pour attaquer les valeurs et les valeurs de l’Islam.

Le film, après cette attaque non acceptable d’un Homme de Cinéma, a été présenté au public français et a eu sa part de public comme un film normal qui traite d’une question normale. Cependant, au Maroc, pour les gardiens du temple et les observateurs de nos valeurs, les policiers du Dieu et de la morale n’ont pas cessé d’alimenter la polémique sur le film qui est devenu une affaire d’Etat pour les uns et une insulte à la culture marocaine et musulmane pour les autres. « Laisser diffuser ce film dans les salles marocaines, est une incitation à la débauche », est la phrase qui n’a cessé de se répéter dans les colonnes du journal de la mouvance islamiste présente dans le parlement marocain. Plusieurs dossiers ont été consacrés par ce journal pour attaquer ce film. Le plus con de ces dossiers s’est basé sur l’analyse de la presse arabe qui a critiqué de façon irresponsable le film, malgré que ces arabes ne comprennent aucunement le dialecte marocain et loin le Français. Pire, ils ne savent même rien sur la culture marocaine, qui pour eux est identique à la leur.

Le comble, c’est quand des journaux dits indépendants comme « Al Jarida Al Oukhra » s’allie avec les islamistes pour attaquer le film. En fait, depuis les critiques et les gros mots mal placés avec lesquels le réalisateur a qualifié le film et la réalisatrice du film lors du festival du film à Tanger, ce journal n’a pas arrêté ces attaques contre le film, à chaque numéro un journaliste essayait de mettre à mort le film, son scénario, ses scènes, sa réalisatrice et ses acteurs.

Le chroniqueur Rachid Nini, du journal Assabah, n’a pas fait mieux lui non plus. Dans sa chronique réservée au film et sa réalisatrice, il s’est donné au satirique pour mettre à plat ce travail cinématographique. Il a conclu son acharnement par proposer à la réalisatrice du film de refaire le film en changeant les rôles, la fille serait juive et le garçon serait musulman. Cette proposition au goût amère montre un peu la schizophrénie qui nous caractérise quand il s’agit des sujets relatifs aux relations entre les sexes.

Et si c’était vraiment le cas, le garçon est musulman et la fille est juive. Les juifs marocains ne seront-ils pas eux aussi fâchés ? Ne sont-ils pas marocains ? Leurs valeurs ne sont-ils pas aussi marocains ? Sinon, ne sont-ils pas plus marocains que les valeurs de l’Islam, si on prend en compte l’arrivée du judaïsme au Maroc ? Ne demanderont-ils pas d’interdire le film pour les mêmes motifs avancés par les critiques négatifs du film ? Ne vont-ils pas menacer de sortir dans les rues pour protester contre le film parce qu’une fille juive aime et fait l’amour avec un musulman ?

De tels jeux de suppositions ne feront jamais le cinéma. Jamais le public ou la critique n’impose un scénario à un réalisateur, une histoire à une scénariste, ou un thème de chanson ou de roman ou d’un tableau à un artiste. La création est individuelle et seuls les auteurs sont concernés par le choix de leurs thèmes. La critique et l’avis du public viennent toujours après la création et nullement avant. Sinon nous allons revenir aux années ou toute chose est imposé pour les pouvoirs totalitaires.

Le comportement du journal Attajdid paraît acceptable considérant la structure de l’idéologie qui est derrière son édition. Selon cette idéologie, qui considèrent la femme comme un sujet tabou, une marchandise et un jouet entre les mains de l’homme qu’il soit son père, son frère ou son mari, refuse catégoriquement toute relation extraconjugale entre les deux sexes et interdit d’ailleurs toute liaison même conjugale entre une musulmane et un juif alors qu’elle tolère le mariage mixte entre un musulman et une juive. Cependant le comportement des journalistes du journal « Al Jarida Al Oukhra » et du chroniquer Rachid Nini dans Assabah, restent inexplicables si on prend en compte le discours que ces journalistes soit disant indépendant et démocrates qui oeuvrent pour la constitution d’un Etat de droit et de droits de l’homme. Le seul analyse valable de ce comportement montre que le discours de Nini dans ces chroniques et de « Al Jarida Al Oukhra » concernant la liberté d’expression n’est que tactique et pas loin d'une conviction.

La vision que rapporte le film, malgré qu’il concerne une minime partie de la population marocaine, en particulier la classe bourgeoise, concerne la jeunesse marocaine tout entière. Si Ali Zaoua le film a traité d’une classe aussi marginalisée Marock traite une autre classe aussi méconnu dans notre société.

Un conseil, allez tous voir le film et faite vous-même votre opinion sur ce film et sur son histoire. Défendez votre droit à l’information, ne laissez plus personne parlez en votre nom. Ce peuple marocain a déjà souffert de parler en son non, vous êtes des membres de ce peuple alors parlez vous-même en votre nom.

A bon entendeur.

Posted by

Arehal

at

4:08 PM

![]() 0

comments

0

comments

That Desert is Our Country

That Desert is Our Country'

Tuareg Rebellions and Competing Nationalisms

in Contemporary Mali

(1946-1996)

An abstract of my PhD thesis

Defended at Amsterdam University, November 6, 2002

If, after reading the abstract below, you would like to read the whole thesis, you can order a copy by mailing

This thesis investigates the causes and origins of the conflict between the Malian state and the Kel Tamasheq (or Tuareg) people inhabiting its Northern regions, which culminated in two rebellions by Tuareg dissidents against the state: one between 1963 and 1964, and a second between 1990 and 1996. Research has not led to one clear-cut answer, concentrating on one specific theme within social science. The thesis argues that the conflict found its origins in a Kel Tamasheq desire to regain political independence, which had been lost after colonial conquest. The conflict was also about the nature of the state and who holds power in it; about racial prejudice and stereotyped images of self and other; about various forms of nationalism; and about political and social developments within Kel Tamasheq society.

After the Second World War, colonial politics worldwide were restructured. In French West Africa and the Maghreb, this restructuring led to the establishment of a new political elite, political parties and a gradual transfer of power in AOF and Morocco from the French to this new elite. At the same time, as the hitherto worthless Sahara started to spout mineral wealth, various conflicts broke out to retrace the Saharan borders - culminating in the French Moroccan war over Mauritania between 1957 and 1958 - while further north-west, a ferocious colonial war of independence ravaged Algeria. In this geo-political configuration, the Moors and Kel Tamasheq literally formed the centre stage as inhabitants of the Sahara. It was in this period that the basis for a future conflict was laid.

What is most striking about this period, is that the multifarious political projects the Kel Tamasheq and Moorish political elite engaged in were all more or less directed against something: Kel Tamasheq and Moorish incorporation in Mali. The OCRS, a French initiative to restructure their Saharan possessions into one colony, sought to keep the Sahara under French tutelage, which precluded Tamasheq and Moorish independence. The Nahda al-Wattaniyya al-Mauritaniyya sought to incorporate the Moorish and (partly) Tamasheq inhabited parts of Mali in either Mauritania or Morocco. Even those leaders who participated in party politics and elections in French Sudan, did so in an attempt to curb the political power of the ‘southern’ political elite. In this period, Kel Tamasheq nationalism was only formulated as a negative nationalism. It was about what they did not want to be - Malian - with hardly any idea what they did want to be.

When in 1960, French Sudan became independent as the Republic of Mali, the various political adventures of the Kel Tamasheq elite had made them highly suspicious in the eyes of the Malian leaders, who were in fear of a Kel Tamasheq rebellion with the support of French troops still present in the region. The Kel Tamasheq attitude towards their incorporation within the new state was, in the eyes of the Malian political elite, as threatening as before independence. Demands about government and administration were made which can be summarised as a demand for virtual autonomy: No state interference in internal affairs; administrators should be Kel Tamasheq or Moor; tribal leaders were to keep their power; Arabic education should be equal to French education. These demands do show a certain contempt for the Malian leaders from the side of the Kel Tamasheq and Moors. This mutual fear and contempt, combined with no small amount of prejudice from both sides, and small personal conflicts growing big in rumour, could only lead to the Malian fear for revolt becoming a sort of self fulfilling prophesy. Indeed, in 1963, the negative wish not to be Malian, led a small group of Kel Adagh men to start an armed uprising which was crushed in blood by an anxious regime. Although it was only partly clear what the rebels wanted, it was clear what they did not want - to be part of a state ruled by black Africans. Only in the 1970s and 1980s was a more positive Kel Tamasheq nationalism created which made clear what it wanted - an independent Kel Tamasheq state.

A few things are striking when looking at the Kel Tamasheq national idea as it was imagined in the 1970s and 1980s by the ishumar - the young Kel Tamasheq migrant workers who shaped both this national idea and the political movement that would fight for it. The first particularity is that a people that organised society and politics on the basis of fictive kinship ties, based its nationalist ideal on territorial notions. The desert they had fled during the droughts of the 1970s and 1980s was nevertheless imagined as a possible fertile national space. There were very specific reasons ‘soil’ was taken as the binding national factor instead of ‘blood’. The Tamasheq nationalists perceived kinship relations in politics as a major obstacle to successful political unification of the Kel Tamasheq nation.

Indeed, the social political structure of the Kel Tamasheq in tewsiten - clans - kept hindering the nationalist movement throughout its existence as various clan based factions fought for political dominancy within the movement. These fights, starting in the mid eighties, would continue during the rebellion and even after the rebellion violence between clans continued to haunt internal politics. Nevertheless, the idea of a Kel Tamasheq country to be united proved just as ineffective and it was abandoned rather quickly. The Kel Tamasheq indigenous to Algeria and Libya, the Kel Hoggar and Kel Ajjer federations, never joined the liberation movement. Already during the 1980s the Kel Tamasheq from Mali and Niger, once united under the name Kel Nimagiler, broke up along the lines of the nation states they sought to overthrow - Mali and Niger. The fact that they garbled the names of Mali and Niger to form their own name as a political entity shows how strongly the idea of the existing nation-states was engraved on their minds.

The second particularity is that the movement incorporated certain ideas on the nature of Tamasheq society and the need to reshape it, which its predecessors - the political leaders of the 1950s and the fighters of Alfellaga - had actively resisted. The USRDA had sought to curb the power of the tribal chiefs, which had been created or strengthened during the colonial period, and to promote the interests of the lower strata of society - the Bellah, or former slaves, and Imghad, or free non-nobles. Although these policies had not been successful, they had formed a major cause for the discontent and subsequent violent rebellion of the Kel Adagh in 1963. Now, only a decade later and the Keita regime gone, the new Tamasheq revolutionaries not only sought to liberate their country from ‘foreign occupation’, they also sought to liberate it from tribal and ‘feudal’ leadership and social relations. The prejudices once held against them were now part of a Kel Tamasheq image of self. In the end, the attempt to rid society from its ‘feudal’ chiefs and social relations failed as much as the attempt to liberate the country from Malian rule. After the ‘fratricidal war’ between the competing rebel movements MPA and ARLA in 1994, and especially after the initiative to final peace in northern Mali in October 1994 from the tribal chiefs of the Bourem Cercle, the power of the tribal leaders was even strengthened at the expense of the revolutionaries. The failure of the movement to incorporate the Bellah as a social group would eventually lead them to join the Ganda Koy, a vigilante movement that sought to end the Tamasheq rebellion through violence.

The conflict between the Malian state and the Kel Tamasheq and Moors forms part of a problem that haunts all of the Sahel, a problem often seen by foreign experts as one of ethnicity, but locally phrased in terms of race.

Perhaps the most interesting side to the racial aspect of the conflict between state and Kel Tamasheq, is that both sides were just as much obsessed with race and that both used racial discourse. One could safely say that Alfellaga was the result of relations between two different political elites based on mutual distrust and negative preconceived stereotyped images. While the Keita regime perceived the Kel Tamasheq as white, anarchist, feudal, lazy, pro-slavery nomads who needed to be civilised, the Kel Tamasheq elite saw the Malian politicians as black, incompetent, untrustworthy slaves in disguise who came to usurp power. These ideas resurfaced with the outbreak of the second rebellion in 1990 and were openly expressed in a mutually hostile discourse on ‘the other’ at the height of the conflict in the summer of 1994, when the Mouvement Patriotique Ganda Koy set out to defend the ‘sedentary black’ population against the ‘white nomad’ threat against national unity.

On a theoretical level one could argue whether racialism is or is not a subcategory of ethnicity. The answer is: It depends on what one means with both terms and from which side one looks at the problem. Racialism is the construction of social groups and identities on the basis of somatic characteristics. Thus, one belongs to a race when oneself and others say so on the basis of one’s appearance. Throughout this book, I have indicated a congruence between the social categories ‘ethnic group’ and ‘nation’ -- a social political group of a size that does not allow all members to know each other, which means it is partly an imaginary community, in which its members recognise each other’s membership on the basis of certain shared cultural traits. The distinction often made between ‘ethnic group’ and ‘nation’ is a political choice stemming from the idea that nation is inherent to ‘nationalism’, which is inherent to ‘state’, which is expressed in the term ‘nation-state’. I have also indicated that I see ethnicity as an ‘ideology’ which forms the glue or imaginary framework of an ethnic group or nation, whereas nationalism, and here I take Gellner’s definition, is ‘primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent’ (Gellner: 1983, 1). In these definitions, race is not a subcategory of ethnicity. One can imagine members of various racial backgrounds to be member of the same nation and this is indeed the case in Kel Tamasheq society.

The Kel Tamasheq are perceived to be racially divided both by themselves as by the Malian government. The Kel Tamasheq themselves discern three somatic types: koual, black; shaggaran, red; and sattefen, greenish black. Each type roughly corresponds with a certain social group within society, but none of these groups is seen as not-Kel Tamasheq. However, the colonial administration, Malian administration of the 1960s, as well as the Ganda Koy movement of the 1990s, only saw two categories of Kel Tamasheq - white and black. These two categories are more often labelled as ‘noble’ and ‘slave’, but with ‘white’ and ‘black’ used as suffixed extensions. Thus, all white Tamasheq are perceived to be noble, which they are not, and all black Kel Tamasheq are seen as of lower status which, again, is not the case, not even when one sees race in Tamasheq society as purely socially constructed.

Illustration: Zeid ag Attaher (middle, white dress), leader of the 1963 rebellion in the Adagh mountains, is paraded through the main street of Kidal in captivity with his lieutenant Ilyas ag Ayyouba in Mai 1964. Kidal Cercle Archives

Posted by

Arehal

at

11:07 AM

![]() 0

comments

0

comments